EVE Online is unique among online games in that the in-game market has significant importance to players, regardless of the game play style they choose to pursue. Whether in high, low or null security, many (probably all) players rely on EVE’s markets to buy and equip ships, sell acquired or produced goods, buy supplies needed for various endeavors, and otherwise fill gaps in the set of things needed to pursue various play styles.

As the market has long been an important feature of EVE, some players have similarly focused on developing tools and strategies to support the use of markets. In the early days, these tools were intended to supplement standard play styles, for example making it easier to track market participation (e.g. positions, open orders) as part of a larger strategy (e.g. mining, production, conquest). However, as the game has grown, so has the sophistication of the markets, and in modern EVE “playing the markets” is a valid play style pursued by many players. Third party tool developers have adopted to these changes as well, with many new tools written explicitly to support profiting from the market. CCP, for their part, has responded by providing more real-time data (e.g. five minute market snapshots), and more visibility into alternative markets (e.g. citadel markets). The combination of new tools and rich data has made it possible to implement many “real life” trading strategies that were previously difficult to execute1.

This book attempts to be a systematic discussion of data driven analysis and trading strategies in EVE’s markets. The strategies we derive here rely on public data provided by CCP. Not all of this data is market data and, in fact, more complicated strategies often rely on non-market data. Regardless, all of this data is publicly available: the strategies we describe here don’t rely on non-public or otherwise proprietary data. We derive concepts and strategies using publicly available tools, and we share our techniques through a number of examples (including source code). While the example code we present here is suitable for illustrative purposes, serious market players will likely want to write custom, optimized code for certain strategies (as the author does).

The remainder of the book is organized as follows:

This chapter explains the mechanics of EVE markets and introduces the various sources of market data we use to develop trading strategies. We also introduce the tools we’ll use in the rest of the book to develop our strategies. We end the chapter with several examples illustrating these tools.

EVE markets are governed by a set of rules which define how orders are placed, how they are matched, and what charges are imposed on the participants in a trade. Market structure in EVE is somewhat unique, but if comparisons to actual financial markets must be made, then EVE markets are most similar to a commodities spot market. Commodities markets trade physical assets (or rather, the right of ownership of assets), much the same as trading occurs in EVE markets. A “spot market” is a market in which assets are exchanged at current prices, as opposed to prices guaranteed by a contract (e.g. futures markets).

Many good descriptions of EVE markets are already available on the web. We recommend reading EVE University’s Trading Introduction for a thorough overview of the interface, important skills and basic mechanics. Rather than recount that description here, we instead provide a more academic treatment of some key aspects of EVE markets below.

There are two order types in EVE markets:

Although this terminology is standard in financial literature, the EVE UI does not use these terms in order placement screens. Generally speaking, if you are placing an order using the “advanced” UI screen (with a duration other than “immediate”), then you are placing a limit order. Otherwise, you are placing a market order. This is true even if your limit order is matched immediately, and has important consequences in terms of trading cost (see below).

Orders are handled “First In, First Out” (FIFO), meaning the sequence of order arrival determines priority for matching with other orders. When a sell order is placed, the items being sold are placed in escrow at the seller’s location. If a sell order is filled, then the sold items are moved to the buyer’s hangar at the seller’s location. In other words, all transactions occur at the seller’s location. This has at least two important consequences for trading strategies:

Market participation from player-owned structures is a relatively recent feature (at time of writing). However, the number of such participants is growing, making it important to consider access risk when buying goods from sellers in these structures.2

Trade prices in EVE markets are determined by order matching rules. Unlike other financial markets, there is no facility for price negotiation or auction, although some of these features exist in secondary markets (e.g. the contract system). Sell orders in EVE have a location, price, quantity and minimum volume. Buy orders have a location, price, quantity, minimum volume and range. A pair of orders match when:

The price at which the transaction occurs must satisfy the following constraints:

The effect of precedence rules means that some care must be taken when pricing orders. For example, suppose a sell limit order is placed for 100 ISK. Suppose further that this order is currently the best available sale price (i.e. the first, lowest price available in the current location). If a buy limit order is then placed for 101 ISK, then this order will match immediately at a price of 101 ISK (not 100 ISK) because the sell order has precedence. A similar behavior occurs when buy limit orders have precedence.

EVE markets impose two fees on orders:

Broker fees are charged as a percentage of the total order value, with the charge normally between 2.5% and 5% (adjusted by standing and the Broker Relations skill). Sales tax is charged as a percentage of the matched order volume multiplied by the match price, with the charge normally between 1% and 2% (adjusted by the Accounting Skill). Sales tax in player-owned structures is determined by the owner and may be lower than the normal range.

There are two important consequences of this fee structure:

Training Broker Relations and Accounting skills is usually mandatory for serious EVE market players as these skills at max training reduce fees by a significant amount.

The primary live source of information for EVE markets is the game client UI which shows a live view of the current order book for each asset, as well as historical pricing information. CCP provides third party developer APIs which expose similar information (see below), but the game client is always the most up to date view of the markets. Several important metrics are visible from the game client including the volume (total assets traded) to date, and the current spread (difference between best buy price and best sell price) between buyers and sellers. The order book for a given asset displays price, volume and location for each order, but does not display the names of market participants. However, the names of market participants are recorded and visible to each counter-party when a transaction is completed. This is a unique feature of EVE markets which is quite different from other financial markets where anonymity is preserved between counter-parties.3 This feature also provides an opportunity for traders to gather more information about other market participants, for example by buying or selling in small quantities to competing bids in order to discover the names of competitors.

Recent EVE expansions have added the ability to create market hubs in player-owned structures. These hubs are added to the market for the region they are located in, allowing orders to be placed from player-owned locations. Although market hubs are now included in regional markets, the player-owned structure itself may not be publicly accessible, or accessibility may change during the course of a day’s market events. As a result:

It is generally safe to sell to orders placed from player-owned structures. However, great care should be taken when buying from orders placed from player-owned structures. Missing location information in out of game data sources is mostly an annoyance right now as workarounds exist to obtain the needed information.

EVE has a large secondary market called the “contract system” which allows for direct player to player exchange of numerous assets, including assets which are not tradable on EVE markets (e.g. fitted ships). We don’t cover the contract system is this book, mainly because there is currently no reliable third party API to gather information about available contracts.

As noted above, market data is visible in the game client in two separate views:

The game client always shows the most recent view of market data. All other data sources (e.g. third party developer sources) lag the game client. It’s also worth noting that the game client is the only EULA-approved way to participate in the market by buying or selling assets.4

Data driven development of trading strategies is usually conducted offline, preferably using several years of market data. CCP has only recently invested effort in making market data easily accessible to third party developers. Historically, market data was gathered through crowd sourcing efforts by scraping cached data stored in the game client.5 Scraped data was then aggregated and made available by third party sites like EVE Central. Asset coverage relied on having enough players interested in regularly viewing certain assets (so that the client cache would be refreshed regularly). The fact that players themselves were providing data also raised concerns about purposely modifying data to affect game play. Despite these limitations and risks, crowd sourced data was the primary source of market data for many years.

In 2015, CCP started providing market history, order book, and market pricing data through their “CREST” API. CREST is a REST-based web API which supports both public and authorized data endpoints. Authorized endpoints use the EVE Single Sign-On service based on OAuth access control. CREST authorization is only used for certain player or corporation related endpoints. Market data can be accessed on CREST without authentication. When market modules were released for player-owned structures (e.g. Citadels), public buy orders placed in these modules were eventually made visible in CREST market data. However, CREST provided no mechanism for resolving the location where these player-owned structures resided, making it difficult to implement the same order matching rules as provided in the game client.

While CREST was an important upgrade for third party developers (as compared to the XML API), CCP significantly modernized third party APIs by releasing the EVE Swagger Interface (ESI) which exposed a new REST-based web API documented with Swagger. Swagger documentation allows the use of many convenient tools for third party developers, such as API browsers and client generators in a variety of languages. Swagger also provides clean support for versioning and authorization, making it much easier for CCP to evolve the API over time. The ESI provides the same market data as in CREST with two important upgrades:

The ESI uses the same OAuth based authorization scheme as CREST. At time of writing, CCP has declared ESI as the API of the future and has deprecated both CREST and the XML API. However, CCP has stated they will keep the XML API and CREST active at least until ESI reaches feature parity. Unless otherwise indicated, examples in this book which require direct access to live market data will use the ESI endpoints.

The remainder of this section describes the main market data ESI endpoints in more detail.

The market history endpoint returns a daily price summary for a given asset type in a given region. In financial modeling terms, this data is similar to daily stock market data. The market history endpoint returns all data from the start of the previous calendar year. Note that data for the current day is typically not available until approximately 0800 UTC the following day.

We’ll use market history to demonstrate the use of the ESI. ESI endpoints follow REST conventions and can always be accessed using the HTTP protocol. For example, the following URL will return market history for Tritanium (type 34) in Forge (region 10000002):

https://esi.tech.ccp.is/latest/markets/10000002/history/?datasource=tranquility&type_id=34The result of this request will be a JSON formatted array of values of the form:

{

"date": "2015-05-01",

"average": 5.25,

"highest": 5.27,

"lowest": 5.11,

"order_count": 2267,

"volume": 16276782035

}where:

What makes the ESI special is the Swagger definition which can be retrieved at:

https://esi.tech.ccp.is/latest/swagger.json?datasource=tranquilityThe Swagger definition is a structured description of the endpoints of ESI, including the name and type of the arguments required, the format of the result, and any authorization that may be required. Tools make use of this definition to automatically generate documentation and API clients. For example, the documentation of the above endpoint can be found here.

In addition to the response body, the ESI also returns several important HTTP response headers. There are three headers you should observe:

The expires field is important for automated collection of data, and for competitive analysis. The tools we describe later in this chapter use expires to drive regular downloads of the data for historical analysis. The expires field also tells you how frequently other market participants can see fresh data (unless they are using the game client).

The market order book endpoints return a view of the current orders for a given region, optionally restricted to a given type. The ESI endpoint to retrieve this data is “get market region orders”. The following URL will retrieve the first page of orders for Tritanium (type 34) in Forge (region 10000002):

https://esi.tech.ccp.is/latest/markets/10000002/orders/?datasource=tranquility&order_type=all&page=1&type_id=34Leaving off type_id=34 will return all orders for all types in the given region. The result of this request will be a JSON formatted array of values of the form:

{

"order_id": 4740968511,

"type_id": 34,

"location_id": 60005599,

"volume_total": 1296000,

"volume_remain": 952089,

"min_volume": 1,

"price": 10,

"is_buy_order": false,

"duration": 90,

"issued": "2017-01-06T22:29:36Z",

"range": "region"

}where:

Order book data is the most current out of game view of the markets and is therefore very important data for many traders. Some important properties about order book data:

Order Book Data Gaps

At various points in time, CCP’s order book endpoints have had gaps in the data they provide. These gaps take the form of orders missing from snapshots. A common pattern is to see an order appear in one snapshot, then disappear, then appear again in a later snapshot. The only cases where an order should exit the order book is if it is canceled or completely filled. Also, an order which leaves the order book should never re-appear as order IDs are unique. We’ll see this problem, and a work-around, in Example 4 below. At time of writing, this problem was still occurring, even in the new ESI based endpoints.

Order book data can also be requested directly from player-owned structures. This is done using the “get markets structures” endpoint. Some player-owned markets are not public, despite their buy orders appearing the regional market, but for those that allow access, the format of the results is identical to the format returned by the “get market region orders” endpoint.

Certain industrial calculations, such as reprocessing tax, require reference price data computed by CCP on a daily basis. This data is available to third party developers using the “get market prices” endpoint. A request to this endpoint will return an array of price data in this format:

{

"type_id": 32772,

"average_price": 501374.49,

"adjusted_price": 502330.89

}where:

We document this endpoint because some strategies discussed in later chapters need to compute certain industrial formulas.

The last market data endpoint we document is the “get universe structure id” endpoint. This is an authenticated endpoint which provides player-owned structure information in the format:

{

"name": "V-3YG7 VI - The Capital",

"solar_system_id": 30000142

}where:

The use for this endpoint is not obvious until one needs to calculate which orders will match in a given region. As described above, the buy orders which match a given sell order are determined by the location of the sell order, and the range and location of each buy order. Therefore, the location of player-owned structures must be known in order to determine whether buy orders submitted at those structures can potentially match. At time of writing, the structure location endpoint is the only third party API which provides access to the location of public player-owned structures. However, as we discussed in Order Book Data Endpoints, the order book for a region may also display buy orders from non-public player-owned structures. The structure location endpoint can not be used to determine the location of these structures unless the (authenticated) caller is authorized to view this data (for example, the caller is a member of the corporation which owns the player-owned structure). Fortunately, there is at least one third party data source that attempts to document the location of non-public structures. We show an example of using the structure location endpoint, as well as other third party data sources, when we construct an order matching algorithm in Example 3 below.

As noted above, CCP currently does not provide an API endpoint for retrieving individual trades. This lack of data is limiting in some cases, but fortunately a portion of trades can be inferred by observing changes in order book data. This approach is effective for trades that do not completely consume a standing limit order. However, limit orders which are removed from the order book can not be distinguished from canceled orders. Thus, the best we can do is rely on heuristics to attempt to estimate trades we can’t otherwise infer. Because CCP publishes daily trade volume, we do have some measure of how close our heuristics match reality. We’ll derive a simple trade estimation heuristic in Example 4 below.

This section provides an introduction to the tools we use to develop strategies in the remainder of the book. As you may have surmised, access to historic and live market data is critically important for analysis, back test, live testing and execution of trading strategies. Many third party sites provide this data in various formats. At Orbital Enterprises, we’ve created our own market data collection tools which we describe below. Our tools, as well as most modern tools (including the EVE Swagger Interface), use web interfaces annotated with Swagger. We therefore provide a brief introduction to Swagger along with a few tips for working with Swagger-annotated endpoints. The EVE Static Data Export (SDE) is another critical resource for third party developers and is needed for some of the strategies we described in this book. The SDE is provided as a raw data export which most players acquire themselves. At Orbital Enterprises, we’ve created an online tool for accessing the SDE which we use in our examples. We describe this tool below. Finally, we briefly introduce Jupyter which has quickly become the de facto data science tool in python. Most of the examples we provide in the book are shared as Jupyter notebooks on our GitHub site.

Orbital Enterprises hosts a market collection service which provides historic and live access to book data and daily market snapshots (the “Order Book Data” and “Market History” endpoints described above, respectively). The service exposes a Swagger annotated API which can be accessed interactively. Historic data is uploaded nightly to Google Storage organized by date. Although the entire history maintained by the site is accessible through the service API, for research and back testing purposes it is usually more convenient to download the data in bulk from the Google Storage site.

About Swagger

Swagger is a configuration language for describing REST-based web services. A Swagger-annotated web site will normally provide a

swagger.jsonfile which defines the services provided by the site. For example, CCP’s EVE Swagger Interface provides thisswagger.jsonfile.The power of Swagger is that the

swagger.jsonfile can be provided as input to tools which automate the generation of documentation and client code. For example, the Swagger UI will generate an interactive UI for any valid Swagger specification. The Swagger Editor has similar capabilities but will also generate clients (and servers) in a variety of programming languages. In most cases, you won’t ever need to manually inspect a Swagger configuration file (much less learn the configuration language) as the tooling does all the hard work for you.In this book, we introduce many APIs using the Swagger UI. You can follow along by browsing to the generic Swagger UI and inserting the URL for the appropriate

swagger.jsonconfiguration file. Most of our code samples are in Python for which we use the Bravado Swagger client generator. We’ll describe Bravado in more detail below.NOTE: the generic Swagger UI will not work with authorized endpoints of the ESI. This is because of the way single sign-on is implemented with the ESI servers. Using authorized endpoints from batch (i.e. non-interactive) code is likewise challenging. One work around is to use a proxy like the ESI Proxy which we use at Orbital Enterprises. This proxy handles OAuth authorization flows automatically, exposing a much simpler interface to our market strategy code.

Let’s use the Swagger UI to introduce the Orbital Enterprises market collection service. You can follow along by browsing to the interactive UI. The UI lists three endpoints:

These endpoints provide the following functions:

Each endpoint can be expanded to view documentation and call the service. For example, expanding the history endpoint reveals:

Filling in the typeID, regionID and date fields with “34”, “10000002” and “2017-01-15” returns the following result (Click “Try it out!”):

The fields in the result match the “Market History” ESI endpoint with following additions:

The book endpoint has a similar interface but since order book snapshots have five minute resolution (based on the cache timer for the endpoint), you can provide a full timestamp. The endpoint will return the latest book snapshot before the specified date/time. Here is the result of the same query above at 10:00 (UTC):

The result is a JSON object where the bookTime field records the snapshot time in milliseconds UTC since the epoch. The orders field list the buy and sell orders in the order book snapshot. The fields in the order results match the “Order Book Data” ESI endpoint with some slight modifications (e.g. timestamps are converted to milliseconds UTC since the epoch) and the addition of typeID and regionID fields.

The livebook endpoint is identical to the book endpoint with two main differences:

The livebook endpoint is most useful for live testing or live execution of trading strategies. We use this endpoint in the later chapters for specific strategies.

As we noted above, the endpoints of the market collection service are most useful for casual testing or for retrieving live data for running strategies. For back testing, it is usually more convenient to download historic data in bulk to local storage. The format of historic data is described on the market collection service site. We introduce python code to read historic data below, either directly from Google Storage, or from local storage.

The EVE Static Data Export is a regularly released static dump of in-game reference material. We’ve already seen data provided by the SDE in the last section - the numeric values for Tritanium (type ID 34) and The Forge (region ID 10000002) were provided by the SDE. The SDE is released by CCP at the Developer Resources Site. The modern version of the SDE consists of YAML formatted files. However, most players find it more convenient to access the SDE from a relational database. Steve Ronuken provides conversions of the raw SDE export to various database formats at his Fuzzworks site.

At Orbital Enterprises, we expose the latest two releases of the SDE as an online service. The underlying data is just Steve Ronuken’s MySQL conversion accessed through a Swagger-annotated web service we provide. If you don’t want to download the SDE yourself, you may want to use our online service instead. Most of the examples we present in this book use the Orbital Enterprises service.

Because our service is Swagger-annotated, there is a ready made interactive service you can use to access the SDE:

The “Release” drop down at the top can be used to select which SDE release to query against (the default is the latest release). At time of writing, we always maintain the two latest releases. We may consider maintaining more releases in the future. Queries against the online service use JSON expressions which are explained on the main site. As an example, let’s look at a query to determine the type ID for Tritanium. First expand the “Inventory” section, then select “/inv/type”:

We’ll search by partial name. Scroll down until the “typeName” field is visible and replace the default query value with { like: '%trit%' }. Then click “Try it out!” (or just hit enter). You’ll see a result similar to the following:

The result includes all types with names that contain the string “trit” (case insensitive). There are many such types, but the first result in this example happens to be the type we were searching for. Most of the market strategies we describe in this book rely on data in the “Inventory” and “Map” sections of the SDE. You can find reasonably recent documentation on the data stored in the SDE at the crowd sources Third Party Developer documentation site. We provide more explicit documentation in the sections below where we use the SDE.

Our method for developing trading strategies could loosely be called “data science”, meaning we use scientific methods and tools for extracting knowledge or insight from raw data. Our main tool is the Python programming language around which a rich set of libraries and methodologies have been developed to support data science. Strategy development is an iterative process, and during the early stages of development it is useful to have tools which are interactive in nature. The Jupyter Project and its predecessor iPython are arguably the most popular interactive tools for data science with Python7. When combined with NumPy and Pandas, the Jupyter platform provides a very capable interactive data science environment. We use this environment almost exclusively in the examples we describe in this book. It is not mandatory, but you’ll get much more out of this book if you install Jupyter yourself and try out some of our examples.

The easiest way to get started with Jupyter is to install Anaconda which is available for Windows, Mac and Linux. Anaconda is a convenient packaging of several open source data science tools for Python (also R and Scala), and also includes Jupyter. Once you’ve installed Anaconda, you can get started with Jupyter by following the quickstart instructions (essentially just jupyter notebook in a shell and you’re ready). If you’re reasonably familiar with Python you can crash ahead and click “New -> Python 3” from your local Jupyter instance to create your first notebook. If you’d like a more comprehensive introduction, we like this tutorial.

Python 2 or Python 3?

If you’re familiar with Python, you’ll know that Python 3 is the recommended environment for new code but, unfortunately, Python 3 broke compatibility with Python 2 in many areas. Moreover, the large quantity of code still written in Python 2 (at time of writing) often leaves developers with a difficult decision as to which environment to use. Fortunately, all of the data science libraries we need for this book have been ported to Python 3. So we’ve made the decision to use Python 3 exclusively in this book. If you must use Python 2, you’ll find that most of our examples can be back-ported without difficulty. However, if you don’t have a strong reason to use Python 2, we recommend you stick with Python 3.

The main interface to Jupyter is the notebook, which is a language kernel combined with code, text, graphs, etc. A language kernel is a back end capable of executing code in a given language. All of the examples we present in this section use the Python 3 language kernel, but Jupyter allows you to install other kernels as well (e.g. Python 2, R, Scala, Java, etc.). The code within a notebook is executed by the kernel with output displayed in the notebook. Text, graphic and other non-code artifacts are handled by the Jupyter environment itself and provide a way to document your work, or develop instructional material (as we’re doing in this book). Notebooks naturally keep a history of your actions (numbered code or text sections) and allow you to edit and re-run previous bits of code. That is, to iterate on your experiments. Finally, notebooks automatically checkpoint (i.e. regularly save your progress) and can be saved and restored at a later time. Make sure you run your notebook on a reasonably powerful machine, however, as deeper data analysis will use up significant memory.

The environment installed from Anaconda has most of the code we’ll need, but from time to time you may need to install other code. In this book, we do this in two cases:

We’ll install a few libraries that typically aren’t included in Anaconda. In fact, we’ll do this almost immediately in the first example below so that we can use the Bravado library for interacting with Swagger-annotated web services.

As we work through the examples, we’ll begin to develop a set of useful libraries we’ll want to use in later examples. We could copy this code to each of our notebooks but that would start to clutter our examples. Instead, we’ll show you how to install these libraries in the default path used by the Jupyter kernel.

We’ll provide instructions for installing missing libraries in the examples where they are needed. Including your own code into Jupyter is a matter of ensuring the path to your packages is included in the “python path” used by Jupyter. If you’re already familiar with Python, you’re free to choose your favorite way of adding your local path. If you’re less familiar with Python, we suggest adding your packages to your local .ipython folder which is created the first time you start a Python kernel in Jupyter. This directory will be created in the home directory of the user which started the kernel.

Python Virtual Environments

Notebooks provide a basic level of code isolation, but all notebooks share the set of packages installed in the Python kernel (as well as any default modifications made to the Python path). This means that any new packages you install (such as those we provide instructions for in some of the examples) will affect all notebooks. This can cause version problems when two different notebooks rely on two different versions of the same package. For this reason, Python professionals try to avoid installing project specific packages in the “global” Python kernel. Instead, the pros create one or more “virtual environments” which isolate the customization needed for specific work. This lets you divide your experiments so that work in one experiment doesn’t accidentally break the work you’ve already done in another experiment.

Virtual environments are an advanced topic which we won’t try to cover here. Interested parties should check out the virtualenv package or read up on using Conda to set up isolated development environments. In our experience, it is easier to use

condato create separate Jupyter environments, but instructions exist for usingvirtualenvto do this as well. We document our Conda setup at the end of this chapter for the curious.

We finish this chapter with code examples illustrating basic analysis techniques we use in the remainder of the book. If you’d like to follow along, you’ll need to install Jupyter as described in the previous section. As always, you can find our code as well as Jupyter notebooks in the code directory in our GitHub project.

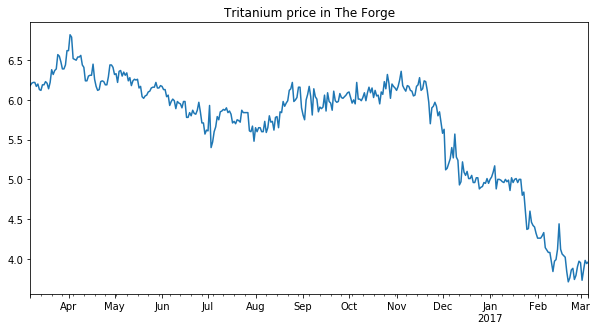

In this example, we’re going to create a simple graph of market history (i.e. daily price snapshots) for a year of data. We’ve arbitrarily chosen to graph Tritanium in Forge. When we’re done, we’ll have a graph like the following:

We’ll use this simple example to introduce basic operations we’ll use throughout this book. If you want to follow along, you can download the Jupyter notebook for this example. Since this is our first example, we’ll be extra verbose in our explanation.

We’ll create our graph in four steps:

We’ll expand on a few variants of these steps at the end of the example to set up for later examples. But before we can do any of this, we need to install Bravado in order to access Swagger-annotated web services. You can install bravado as follows (do this before you start Jupyter):

$ pip install bravadoInstalling Bravado on Windows

On Windows, you may see an error message about missing C++ tools when building the “twisted” library. You can get these tools for free from Microsoft at this link. Once these tools are installed, you should be able to complete the install of bravado.

Once you’ve installed Bravado, you can start Jupyter and create a Python 3 notebook. Almost every notebook we create will start with an import preamble that brings in a few key packages. So we’ll start with this Jupyter cell:

The first thing we need to do is use the SDE to lookup the type and region ID, respectively, for “Tritanium” and “The Forge”. Yes we already know what these are from memory; we’ll write the code anyway to demonstrate the process. The next two cells import Swagger and create a client which will connect to the online SDE hosted by Orbital Enterprises:

The config argument to the Swagger client turns off response validation and instructs the client to return raw Python objects instead of wrapping results in typed Python classes. We turn off response validation because some Swagger endpoints return slightly sloppy but otherwise usable responses. We find working with raw Python objects to be easier than using typed classes, but this is a matter of personal preference. We’re now ready to look up type ID which is done in the following cell:

We use the getTypes method on the Inventory endpoint, selecting on the typeName field (using the syntax described here). The result is an array of all matches to our query. In this case, there is only one type called “Tritanium” which is the first element of the result array.

Pro Tip: Getting Python Function Documentation

If you forget the usage of a Python function, you can bring up the Python docstring using the syntax

?function. Jupyter will display the docstring in a popup. In the example above, you would use?sde_client.Inventory.getTypesto view the docstring.

Similarly, we can use the Map endpoint to lookup the region ID for “The Forge”:

Of course, we only need the type and region ID, so we’ll tidy things up in the next cell and extract the fields we need into local variables:

Next, we need to create a date range for the days of market data we’d like to display. This is straightforward using datetime and the Pandas function date_range:

With these preliminaries out of the way, we’re now ready to start extracting market data. To do this, we’ll need a Swagger client pointing to the Orbital Enterprises market data service. As a test, we can call this service with the first date in our date range:

We call the history method on the MarketData endpoint passing a type ID, region ID, and the date we want to extract. This method can only be used to lookup data for a single date, so the result is a single JSON object with the requested information. The history endpoint may not have any data for a date we request (e.g. because the date is too far in the past, or the service has not yet loaded very recent data). It is therefore useful to check what happens when we request a missing date:

The result is a nasty stack trace due to an HTTPNotFound exception. We’ll need to handle this exception when we request our date range in case any data is missing.

Using a Response Object Instead of Exceptions

The Bravado client provides an alternative way to handle erroneous responses if you’d prefer not to handle exceptions. This is done by requesting a

responseobject as the result of a call. To create aresponseobject, change your call syntax from:result = client.Endpoint.method(...).result()to:

result, response = client.Endpoint.method(...).result()The raw response to a call will be captured in the

responsevariable which can be inspected for errors as follows:if response.status_code != 200: # An error occurred ...You can either handle exceptions or use response objects according to your preference. We choose to simply handle exceptions in this example.

Now that we know how to retrieve market history for a single day, we can retrieve our entire date range with a simple loop:

The result is an array of market history, hopefully for every day we requested (the last day in the range will usually be missing because the market data service hasn’t loaded it yet). Now that we have our market data, we need to turn it into a plot. We’ll use a Pandas DataFrame for this. If you haven’t already, you’ll want to read up on Pandas as we’ll use its data structures and functions throughout the book. There are many ways to create a DataFrame but in our case the most convenient approach will be to base our DataFrame on the array of market data we just loaded. All that is missing is an index for the DataFrame. The natural choice here is to use the date field in each day of market history. However, these dates are not in a format understood by Pandas so we’ll have to convert them. This is easy to do using datetime again. Here’s an example which converts the date field from the first day of market history:

We’ll turn the converter into a function for convenience, then create our DataFrame:

Last but not least, we’re ready to plot our data. Simple plots are very easy to create with a DataFrame. Here, we plot average price for our date range:

And that’s it! You’ve just created a simple plot of market history.

We walked through this example in verbose fashion to demonstrate some of the key techniques we’ll need for analysis later in the book. As you develop your own analysis, however, you’ll likely switch to an iterative process which may involve executing parts of a notebook multiple times. You’ll want to avoid re-executing code to download data unless absolutely necessary as more complicated analysis will require order book data which is substantially larger than market history. If you know you’ll be doing this often, you may find it more convenient to download historic data to your local disk and read the data locally instead of calling a web service.

All data available on the market data service site we used in this example is uploaded daily to the Orbital Enterprises Google Storage site (you can find full documentation here). Historic data is organized by day. You can find data for a given day at the URL: https://storage.googleapis.com/evekit_md/YYYY/MM/DD. At time of writing, six files are stored for each day8:

| File | Description |

|---|---|

| market_YYYYMMDD.tgz | Market history for all regions and types for the given day. |

| interval_YYYYMMDD_5.tgz | Order book snapshots for all regions and types for the given day. |

| market_YYYYMMDD.bulk | Market history in “bulk” form for all regions and types for the given day. |

| interval_YYYYMMDD_5.bulk | Order book snapshots in “bulk” form for all regions and types for the given day. |

| market_YYYYMMDD.index.gz | Market history bulk file index for the given day. |

| interval_YYYYMMDD_5.index.gz | Order book snapshot bulk file for the given day. |

We’ll discuss the market history files here, and leave the order book files for the next example.

Historic market data is optimized for two use cases:

The tar’d archive files (e.g. tgz files), when extracted, contain files of the form market_TYPE_YYYYMMDD.history.gz where TYPE is the type ID for which history is recorded in the file, and YYYYMMDD is the date of the market history. The content of each file is a comma-separated table of market history for all regions on the given day. Let’s look at a sample file:

$ wget -q https://storage.googleapis.com/evekit_md/2017/01/01/market_20170101.tgz

$ ls -lh market_20170101.tgz

-rw-r--r--+ 1 mark_000 mark_000 2.2M Jan 31 02:55 market_20170101.tgz

$ tar xvzf market_20170101.tgz

... about 10000 files extracted ...

$ zcat market_34_20170101.history.gz | head -n 10

34,10000025,13,2.89,4.50,4.00,7319512,1483228800000

34,10000027,1,0.28,0.28,0.28,155501,1483228800000

34,10000028,44,4.80,4.80,4.80,12336476,1483228800000

34,10000029,19,2.00,5.00,3.50,41728843,1483228800000

34,10000030,735,4.60,4.76,4.64,419745507,1483228800000

34,10000016,964,3.98,4.66,4.36,225219117,1483228800000

34,10000018,4,2.03,2.03,2.03,3046465,1483228800000

34,10000020,367,4.50,4.50,4.50,264925396,1483228800000

34,10000021,1,4.48,4.48,4.48,4500000,1483228800000

34,10000022,3,1.51,1.51,1.51,10145393,1483228800000The columns in the file are:

The data stored in the bulk files has the same format but is organized differently in order to support efficient online requests using an HTTP range header. We construct the bulk file by concatenating each of the individual compressed market files. This results in a file with roughly the same size as the archive, but which needs an index in order to recover market history for a particular type. This is the purpose of the market index file, which records the byte range for each market type stored in the bulk file. Here are the first ten lines for the index file for our sample date:

$ curl -s https://storage.googleapis.com/evekit_md/2017/01/01/market_20170101.index.gz | zcat | head -n 10

market_18_20170101.history.gz 0

market_19_20170101.history.gz 984

market_20_20170101.history.gz 1928

market_21_20170101.history.gz 3678

market_22_20170101.history.gz 4439

market_34_20170101.history.gz 5431

market_35_20170101.history.gz 8953

market_36_20170101.history.gz 12396

market_37_20170101.history.gz 15820

market_38_20170101.history.gz 19108Thus, to recover type 34 we need to extract bytes 5431 through 8952 (inclusive) from the bulk file. We can do this by using an HTTP “range” request as follows:

$ curl -s -H "range: bytes=5431-8952" https://storage.googleapis.com/evekit_md/2017/01/01/market_20170101.bulk | zcat | head -n 10

34,10000025,13,2.89,4.50,4.00,7319512,1483228800000

34,10000027,1,0.28,0.28,0.28,155501,1483228800000

34,10000028,44,4.80,4.80,4.80,12336476,1483228800000

34,10000029,19,2.00,5.00,3.50,41728843,1483228800000

34,10000030,735,4.60,4.76,4.64,419745507,1483228800000

34,10000016,964,3.98,4.66,4.36,225219117,1483228800000

34,10000018,4,2.03,2.03,2.03,3046465,1483228800000

34,10000020,367,4.50,4.50,4.50,264925396,1483228800000

34,10000021,1,4.48,4.48,4.48,4500000,1483228800000

34,10000022,3,1.51,1.51,1.51,10145393,1483228800000Note that this is the same data we extracted from the downloaded archive.

As an illustration of code which makes use of downloaded data (if available), we’ll conclude this example with an introduction to library code we’ll be using in later examples. You can find our library code in the code folder on our GitHub site. You can incorporate our libraries into your notebooks by copying the evekit folder (and all its sub-folders) to your .ipython directory (or another convenient directory in your Python path).

We can re-implement this first example using the following modules from our libraries:

evekit.online.Download - download archive files to local storage.evekit.reference.Client - make it easy to instantiate Swagger clients for commonly used services.evekit.marketdata.MarketHistory - make it easy to retrieve market history in various forms.evekit.util - a collection of useful utility functions.You can view this Jupyter notebook to see this example implemented with these libraries. We didn’t actually download any archives in the original example, but we include a download in the re-implemented example to demonstrate how these libraries function.

In this example, we turn our attention to analyzing order book data. The goal of this example is to compute the average daily spread for Tritanium in The Forge region for a given date. Spread is defined as the difference in price between the lowest priced sell order, and the highest priced buy order. Among other things, spread is an indication of whether market making will be profitable for a given asset, but we’ll get to that in a later chapter. The average daily spread is the average of the spreads for each order book snapshot. At time of writing, order book snapshots are generated every five minutes. So the average daily spread is just the average of the spread computed for each of the 288 book snapshots which make up a day.

We’ll start by getting familiar with the order book data endpoint on the Orbital Enterprises market data service site:

There are actually two endpoints, but we’re only looking at the historic endpoint for now. We’ll cover the “latest book” endpoint in a later chapter. As with the market history endpoint, the order book endpoint expects a type ID, a region ID, and a date. However, the date field may optionally include a time. The order book snapshot returned by the endpoint will be the latest snapshot before the specified time. Here’s an example of the result returned with type ID 34 (Tritanium), region ID 10000002 (The Forge), and timestamp 2017-01-01 12:02:00 UTC (note that this endpoint can parse time zone specifications properly):

{

"bookTime": 1483272000000,

"orders": [

{

"typeID": 34,

"regionID": 10000002,

"orderID": 4708935394,

"buy": true,

"issued": 1481705362000,

"price": 5,

"volumeEntered": 200000000,

"minVolume": 1,

"volume": 43345724,

"orderRange": "solarsystem",

"locationID": 60002242,

"duration": 90

},

{

"typeID": 34,

"regionID": 10000002,

"orderID": 4734310642,

"buy": true,

"issued": 1483260173000,

"price": 4.9,

"volumeEntered": 100000000,

"minVolume": 1,

"volume": 99928181,

"orderRange": "station",

"locationID": 60015026,

"duration": 90

},

... many more buy orders ...

{

"typeID": 34,

"regionID": 10000002,

"orderID": 4733287152,

"buy": false,

"issued": 1483171052000,

"price": 4.69,

"volumeEntered": 5612007,

"minVolume": 1,

"volume": 747984,

"orderRange": "region",

"locationID": 60007498,

"duration": 90

},

{

"typeID": 34,

"regionID": 10000002,

"orderID": 4734141760,

"buy": false,

"issued": 1483239477000,

"price": 4.77,

"volumeEntered": 46906,

"minVolume": 1,

"volume": 46906,

"orderRange": "region",

"locationID": 60003079,

"duration": 90

},

... many more sell orders ...

],

"typeID": 34,

"regionID": 10000002

}The bookTime field reports the actual timestamp of this snapshot in milliseconds UTC since the epoch. In this example, the book time is 2017-01-01 12:00 UTC because that is the latest book snapshot at requested time 2017-01-01 12:02 UTC.

Pro Tip: Converting Timestamps

If you plan to work with Orbital Enterprises raw data on a frequent basis, you’ll want to find a convenient tool for converting millisecond timestamps to human readable form. The author uses the Utime Chrome plugin for quick conversions. You’ll only need this when browsing the data manually. The evekit libraries (should you choose to use then) handle these conversions for you.

Orders in the order book are contained in the orders array with buy orders appearing first, followed by sell orders. To make processing easier, buy orders are sorted with the highest priced orders first; and, sell orders are priced with the lowest priced orders first. Order sorting simplifies spread computations but there’s a catch in that a spread is only valid if the highest buy and lowest sell are eligible for matching (except for price, of course). That is, the spread is not always the difference between the highest price buy and the lowest price sell, because those orders may not be matchable. We see this behavior in the sample output above: the highest price buy order is for 5 ISK, but the lowest price sell order is 4.69 ISK. Even though the resulting spread would be negative, which can never happen according to market order matching rules, the orders are valid because they can not match: the buy order is ranged to the solar system Otanuomi but the sell order was placed in the Obe solar system. For the sake of simplicity, we’ll limit this example to computing the spread for buy and sell orders at a given station. We’ll use “Jita IV - Moon 4 - Caldari Navy Assembly Plant” which is the most popular station in the Forge region and has location ID 60003760. In reality, there may be many spreads for a given type in a given region as different parts of the region may have unique sets of matching orders. Computing proper spreads in this way would also require implementing a proper order matching algorithm which we’ll leave to a later example. For strategies like market making, however, one is normally only concerned with “station spread” which is what we happen to be computing in this example.

We assume you’ve already installed bravado as described in Example 1. If you haven’t installed bravado, please do so now. As always, you can follow along with this example by downloading the Jupyter notebook.

The first two cells of this example important standard libraries and configure properties such as type_id, region_id, station_id and compute_date which is set to the timestamp of the first order book snapshot we wish to measure. Note that we use the EveKit library to retrieve an instance of the SDE client:

We can use the Orbital Enterprises market data client to extract the first book snapshot:

Buy and sell orders are conveniently sorted in the result. We use a filter extract these orders by type (e.g. buy or sell) and station ID, then implement a simple spread calculation function to calculate the spread for a set of buys and sells:

Finally, we’re ready to compute spread for all 5-minute snapshots on the target date. We can do this with a simple loop, requesting the next snapshot at each iteration and adding the spread to an array of values which are averaged at the end:

And with that, you’ve just computed average daily spread.

As in the first example, we now turn to order book data formats for local storage. You can find order book files for a given day at the URL: https://storage.googleapis.com/evekit_md/YYYY/MM/DD. Three files are relevant for order book data:

| File | Description |

|---|---|

| interval_YYYYMMDD_5.tgz | Order book snapshots for all regions and types for the given day. |

| interval_YYYYMMDD_5.bulk | Order book snapshots in “bulk” form for all regions and types for the given day. |

| interval_YYYYMMDD_5.index.gz | Order book snapshot bulk file for the given day. |

Note that book data files are significantly larger than market history files as they contain every order book snapshot for every type in every region on a given day. At time of writing, a typical book index file is about 100KB which is manageable. However, bulk files are typically 500MB while zipped archives are 250MB. A year of data is about 90GB of storage. By the way, the 5 in the file name indicates that these are five minute snapshot files. In the future, we may generate snapshots with different intervals. You can easily generate your own sampling frequency using the five minute samples as a source since these these are currently the highest resolution samples available.

The tar’d archive files (e.g. tgz files), when extracted, contain files of the form interval_TYPE_YYYYMMDD_5.book.gz where TYPE is the type ID for which order book snapshots are recorded, and YYYYMMDD is the date on which the snapshots were recorded. The content of each file is slightly more complicated and is explained below. Here is the contents of a sample file:

$ wget -q https://storage.googleapis.com/evekit_md/2017/01/01/interval_20170101_5.tgz

$ ls -lh interval_20170101_5.tgz

-rw-r--r--+ 1 mark_000 mark_000 223M Jan 2 03:43 interval_20170101_5.tgz

$ tar xvzf index_20170101_5.tgz

... about 10000 files extracted ...

$ zcat interval_34_20170101_5.book.gz | head -n 10

34

288

10000025

1483228800000

10

12

4730662577,true,1482974353000,4.85,100000000,1,46444066,station,61000807,30

4732527006,true,1483117790000,4.50,100000000,1,99774417,station,61000912,90

4733368217,true,1483178139000,4.45,340000,1,340000,solarsystem,1021334931934,30

4724371732,true,1482505562000,4.05,10000000,1,4636157,2,61000912,90The first two lines indicate the type contained in the file, in this case Tritanium (type ID 34), and the number of snapshots collected for each region, in this case 288 (a snapshot every five minutes for 24 hours). The remainder of the file organizes snapshots per region and is organized as follows:

FIRST_REGION_ID

FIRST_REGION_FIRST_SNAPSHOT_TIME

FIRST_REGION_FIRST_SNAPSHOT_BUY_ORDER_COUNT

FIRST_REGION_FIRST_SNAPSHOT_SELL_ORDER_COUNT

FIRST_REGION_FIRST_SNAPSHOT_BUY_ORDER

...

FIRST_REGION_FIRST_SNAPSHOT_SELL_ORDER

...

FIRST_REGION_SECOND_SNAPSHOT_TIME

...

SECOND_REGION_ID

...The columns for each order row are:

As with market history, the bulk files are simply the concatenation of the per-type book files together with an index to allow efficient range requests. We can retrieve the same data as above by first consulting the index file:

$ curl -s https://storage.googleapis.com/evekit_md/2017/01/01/interval_20170101_5.index.gz | zcat | head -n 10

interval_18_20170101_5.book.gz 0

interval_19_20170101_5.book.gz 143131

interval_20_20170101_5.book.gz 234988

interval_21_20170101_5.book.gz 447702

interval_22_20170101_5.book.gz 522083

interval_34_20170101_5.book.gz 619717

interval_35_20170101_5.book.gz 1236236

interval_36_20170101_5.book.gz 1780447

interval_37_20170101_5.book.gz 2208243

interval_38_20170101_5.book.gz 2651627Then sending a range request, in this case to extract bytes 619717 through 1236236 (inclusive):

$ curl -s -H "range: bytes=619717-1236236" https://storage.googleapis.com/evekit_md/2017/01/01/interval_20170101_5.bulk | zcat | head -n 10

34

288

10000025

1483228800000

10

12

4730662577,true,1482974353000,4.85,100000000,1,46444066,station,61000807,30

4732527006,true,1483117790000,4.50,100000000,1,99774417,station,61000912,90

4733368217,true,1483178139000,4.45,340000,1,340000,solarsystem,1021334931934,30

4724371732,true,1482505562000,4.05,10000000,1,4636157,2,61000912,90The format of book files is currently optimized for selection by type, which may not be appropriate for all use cases. It is usually best to download the book files you need, and re-organize them according to your use case. The EveKit libraries provide support for basic downloading, including only downloading the types or regions you want.

The second part of the Jupyter Notebook for this example illustrates how to download and compute average spread using the EveKit libraries and Pandas. This can be done in four steps:

As described in the introductory material in this chapter, sell limit orders do not specify a range. Buyers explicitly choose which sell orders they wish to buy from and, if the buyer’s price is at least as large as the seller’s price, then the order will match at the location of the seller (but at the maximum of the buyer’s price and the seller’s price; also, the lowest priced asset at the target station always matches first). When selling at the market, however, the matching rules are more complicated because buy limit orders specify a range. In order to figure out whether two orders match, the location of the buyer and seller must be compared against the range specified in the buyer’s order.

The analysis of more sophisticated trading strategies will eventually require that you determine which orders you can sell to in a given market. Thus, in this example, we show how to implement a “buy order matching” algorithm. Buy matching boils down to determining the distance between the seller and potentially matching buy orders. We show how to use map data from the Static Data Export (SDE) to compute distances between buyers and sellers (or rather, the distance between the solar systems where their stations reside). One added complication is that player-owned structures are not included in the SDE. Instead, a separate data service must be consulted to map a player-owned structure to the solar system where it is located. We show how to use one such service in this example. Finally, we demonstrate the use of our matching algorithm against an order book snapshot. As always, you can follow along with this example by downloading the Jupyter Notebook.

NOTE

This example requires the

scipypackage. If you’ve installed Anaconda, then you should already havescipy. If not, then you’ll need to install it using your favorite Python package manager.

Let’s start by looking at a function which determines whether a sell order placed at a particular station can match a given buy order visible at the same station. We need the following information to make this determination:

Strictly speaking, the region ID is not required as it can be inferred from station ID. We include the region ID here as a reminder that trades can only occur within a single region: EVE does not currently allow cross-region market trading. Henceforth, unless otherwise stated, we assume the selling and buying stations are within the same region.

With the information above, we can write the following order matching function:

def order_match(sell_station_id, buy_station_id, order_range):

"""

Returns true if a sell market order placed at sell_station_id could be matched

by a buy order at buy_station_id with the given order_range

"""

# Case 1 - "region"

if order_range == 'region':

return True

# Case 2 - "station"

if order_range == 'station':

return sell_station_id == buy_station_id

# Remaining checks require solar system IDs and distance between solar systems

sell_solar = get_solar_system_id(sell_station_id)

buy_solar = get_solar_system_id(buy_station_id)

# Case 3 - "solarsystem"

if order_range == 'solarsystem':

return sell_solar == buy_solar

# Case 4 - check jump range between solar systems

jump_count = compute_jumps(sell_solar, buy_solar)

return jump_count <= int(order_range)There are two functions we need to implement to complete our matcher:

get_solar_system_id - maps a station ID to a solar system ID.compute_jumps - calculates the shortest number of jumps to get from one solar system to another.We can implement most parts of these functions using the SDE. However, if either station is a player-owned structure, then the SDE alone won’t be sufficient. Let’s first assume neither station is player-owned and implement the appropriate functions. For this example, we’ll load our Jupyter notebook with region and station information as in previous examples. We’ll also include type and date information so that we can download an order book snapshot for Tritanium to use for testing:

The next cell contains our order matcher, essentially identical to the code above:

Let’s start with the get_solar_system_id function. Since we’re assuming that neither station is a player-owned structure, this function will be just a simple lookup from the SDE:

Implementing the compute_jumps function, however, is a bit more complicated. In order to calculate the minimum number of jumps between a pair of solar systems, we first need to determine which solar systems are adjacent, then we need to compute a minimal path using adjacency relationships. Fortunately, the scipy package provides a library to help solve this straightforward graph theory problem. Our first task is to build an adjacency matrix indicating which solar systems are adjacent (i.e. connected by a jump gate). We start by retrieving all the solar systems in the current region using the SDE:

The solar_map dictionary will maintain a list of solar system IDs which share a jump gate. The next bit of code populates the dictionary by fetching solar system jump gates from the SDE:

With adjacency determined, we’re now ready to build an adjacency matrix. An adjacency matrix is a square matrix with dimension equal to the number of solar systems, where the value at location (source, destination) is set to 1 if source and destination share a jump gate, and 0 otherwise. Once we’ve created our adjacency matrix, we use it to initialize a scipy matrix object needed for the next step:

The last step is to call the appropriate scipy function to build a shortest paths matrix from the adjacency matrix. The result is a matrix where the value at location (source, destination) is the number of solar system jumps required to move from source to destination:

With the shortest path matrix complete, we can now implement the compute_jumps function:

The Jupyter notebook includes a few simple tests to show that this function is working properly. Now that our basic matching algorithm is complete, we can test it on the book snapshot we extracted. In this case, we’ll test which buy orders could potentially match a sell order placed at our target station. This can be done with a simple loop:

Although we’ve found several matches, note that there are several orders for which the solar system ID can not be determined. This is because these orders have been placed at a player-owned structure. Another way you can tell this is the case is by looking at the location ID for these orders. Location IDs greater than 1,000,000,000,000 (1 trillion) are generally player-owned structures. Let’s now turn our attention to resolving the solar system ID for player-owned structures. The CCP supported mechanism is to use the Universe Structures ESI Endpoint. This endpoint returns location information for a player-owned structure if your authenticated account is authorized to access that structure. If your account is not authorized to access a given structure, then you can’t view location information, even if the buy orders placed from the structure appear in the public market. This is a somewhat inconvenient inconsistency in EVE’s market rules, but fortunately there are third party sites which can be used to discover the location of otherwise inaccessible player-owned structures. We use one such site in this example, primarily because it doesn’t require authentication and setting up proper authentication to use the supported ESI endpoint is beyond the scope of this example.

The third party site we’ll use in this example is the Citadel API site, which uses a combination of the ESI and crowd-sourced reporting to track information about player-owned structures. This site provides a very simple API for retrieving structure information based on structure ID. You can create a client for this site using the EveKit libraries:

The relevant information for our purposes is systemId which is the solar system ID. With this service, we can implement an improved get_solar_system_id:

which fixes any missing solar systems when we attempt to match orders in our snapshot:

And with that, we’ve implemented our buy order matcher.

As currently implemented, our matcher makes frequent calls to the SDE which can be inefficient for analyzing large amounts of data. The remainder of the Jupyter notebook for this example describes library support for caching map information for frequent access. We end the example with a convenient library function that implements our buy matcher in it’s entirety, including resolving solar system information from alternate sources.

The CCP provided EVE market data endpoints provide quote and aggregated trade information. For some trading strategies (e.g. market making), finer grained detail is often required. For example, which trades matched a buy market order versus a sell market order? What time of day do most trades occur? Because CCP does not yet provide individual trade information, we’re left to infer trade activity ourselves. In some cases, we can deduce trades based on changes to existing marker orders, as long as those orders are not completely filled (i.e. appear in the next order book snapshot). Orders which are removed, however, could either be canceled or completely filled by a trade. As a result, we’re left to use heuristics to infer trading behavior.

In this example, we develop a simple trade inference heuristic. This will be our first taste of the type of analysis we’ll perform many times in later chapters in the book. Specifically, we’ll need to derive a hypotheses to explain some market behavior; we’ll need to do some basic testing to convince ourselves we’re on the right track; then, we’ll need to perform a back test over historical data to confirm the validity of our hypothesis. Of course, performing well in a back test is no guarantee of future results, and back tests themselves can be misused (e.g. over-fitting). A discussion of proper back testing is beyond the scope of this example. We’ll touch on this topic as needed in later chapters (there are also numerous external sources which discuss the topic).

We’ll use a day of order book snapshots for Tritanium in The Forge to test our heuristic. This example dives more deeply into analysis than previous examples. We’ll find that the “obvious” choice for estimating trades does not work very well, and we’ll briefly discuss a hypothesis on how to make a better choice. We’ll show how to perform a basic analysis of our hypothesis, then show a simple back test evaluating our strategy. You can follow along with this example by downloading the Jupyter Notebook.

Earlier in this chapter we noted that one problem with order book data is that CCP’s endpoint sometimes omits orders leading to gaps. Since trades are inferred from order book snapshots, we first need to deal with the gapping problem. Such issues are not uncommon in the real world of data science. Fortunately, we can fix most of these problems although we don’t have enough information to claim we’ve fixed all such gaps. Once we’ve applied our fix to the data, we continue with our analysis on trade estimation.

The nature of the gapping problem is that, occasionally, orders will disappear from order book snapshots, only to re-appear again in a later snapshot. This can confuse our trade heuristic which attempts to infer trades by looking at differences between subsequent snapshots. We can illustrate this problem by looking for orders with this behavior. In fact, we don’t have to look much further than the first snapshot in this particular example. The following code finds orders which are missing from some snapshots:

If we take a look at the first order we found (e.g. 4720076544), we can verify this order is missing by checking the issue date:

The issue date is clearly before our target date so this order should definitely be in the first snapshot. In fact, in turns out this order is missing from many snapshots:

To fix this problem, we’ve added a “fill_gaps” option to the EveKit order book loader which will backfill gaps when it’s clear an order is missing. When the order loader detects a gap, it works backwards from the snapshot where the gap was detected, inserting the order into any missing snapshot until it finds a snapshot with a timestamp before the issue date of the order, or it finds a snapshot where the order already exists.

If we reload the order book, this time with fill_gaps=True, we see that all gaps have been repaired:

Henceforth, we’ll use the “fill_gaps” feature any time having gap free data is important. Let’s move now to inferring trades from the order book.

A quick review of EVE market mechanics tells us that once an order is placed, it can only be changed in the following ways:

Since a partially filled order is the only unambiguous indication of a trade, let’s start by building our heuristic to catch those events. The following function does just that:

This function reports the set of inferred trades as a DataFrame:

Note that the trade price may not be correct as market orders only guarantee a minimum price (in the case of a sell), or a maximum price (in the case of a buy). The actual price of an order depends on the price of the matching order and could be higher or lower. Note also that we can only be certain of location for sell orders since these always transact at the location of the seller, unless a buy order happens to list a range of station.

The best way to test our heuristic is to compute trades for a day where market history is also available. We’ve done that in this example so that we can load the relevant market history and compare results. From that comparison, we see that partial fills only account for a fraction of the volume for our target day:

In this example, partial fills account for about 40% of the daily volume for this day. That leaves us to estimate complete fills, but it also tells us this is an important estimate as more than half of this day’s trading volume came from complete fills. There are many ways we can estimate complete fills, but a simple strategy is to start with the naive approach of assuming any order which is removed between book snapshots must be a completed fill. We know this will rarely be correct, but it is possible that the number of removed orders which are actually cancels is small enough to not be significant. Let’s update our trade heuristic to capture these fills in addition to the partial fills we already capture:

How does this version compare?

The naive approach overshoots volume by almost 200%. This tells us that in fact a significant amount of removed order volume is due to cancels (or expiry) instead of complete fills. The results also show that we’re only able to recover about 30% of the trades for the day. This is important because the naive algorithm captures all possible trades visible in the data and yet still misses a significant number (by count). This tells us that a substantial number of trades are occurring between snapshots. If these trades are partial fills, then we’re already capturing the volume but we have no mechanism to capture the individual trades. It’s also possible that limit orders are being placed and completely filled between snapshots. We have no way to capture these trades as they are not visible in the data. Given the short duration between snapshots (5 minutes at time of writing), it seems unlikely we’re missing very short lived limit orders.

Since we can’t match trade count, we’ll instead focus on trying to more closely match volume for the day. We know that some removed orders must be cancels and not complete fills. Perhaps this is related to volume. Let’s take a look at a histogram of the volume of the data from inferred trades (i.e. trades which are either complete fills or cancels):

From this plot, we can see that there are very clear outliers. In fact, it looks like trades with volume above 500 million may actually be cancels instead of trades. Why would we draw this conclusion? Because trades this large would represent a substantial portion of daily volume. In fact, by doing a simple calculation in the next cell, we see that the sum of the volume of trades above 500 million accounts for about 80% of total daiily volume. Morevoer, removing these trades from our set of inferred trades gives us an inferred volume very close to actual volume.

This analysis suggests a very simple strategy for distinguishing complete fills from cancels:

If we adopt this strategy, what value should we use for a threshold? We can’t conclude that 500 million will always be an appropriate threshold. For one thing, each asset type will almost certainly have a different threshold. For another, as volume changes daily, it’s likely the appropriate threshold will change daily as well. A better choice might be to base our threshold on a percentage of daily volume. That way, our threshold will adjust as volume changes over time. If we arbitrarily choose our threshold for this example as a starting point, then our target threshold is approximatley 4%. We don’t have much data to suggest that 4% of daily volume is the right threshold. But, for the sake of completing this example, let’s assume this is the correct ratio. This is our final version of our trade inference function which treats orders above a certain volume as cancels:

We’ll now turn to back testing our new strategy. A “back test” is simply an evaluation of an algorithm over some period of historical data. For this example, we’ll test our strategy over the thirty days prior to our original test date. The example Jupyter Notebook provides cells you can evaluate to download sufficient market data to local storage. We strongly recommend you do this as book data will take significantly longer to fetch on demand over a network connection.

Since we may want to be able to infer trades on a day for which we don’t yet have historic data (e.g. the current day), we’ll set the volume threshold for the current day to be 4% of the average volume for the preceeding five days (i.e. five day moving average of daily volume). Market making, discussed in a later chapter, is an example strategy where it’s important to be able to infer trades before historic data is tabulated for the day. Now that we have all required data, our back test is then a simple iteration over the appropriate date range:

We capture the results in a DataFrame for further analysis:

We can then view the results of our test comparing inferred trade count and volume with historic values on the same days. The following graphs show the results of this comparison (values near zero are better):

We know that we are unlikely to capture trade count accurately and the first plot confirms those results. However, the volume plot is surprisingly good, with many days within 20% of actual which is likely good enough for our use. If computing trades before history is available is less important, then another strategy would be to sort inferred trades descending by volume and iteratively remove large trades until within some set threshold of actual historic volume. We leave that variant as an exercise for the reader.

The EveKit libraries do not include any explcit support for trade analysis such as we described above. The highly heuristic nature of this analsyis makes it difficult to provide a standard offering. As we’ll see in later chapters, the basic analysis above can be adapted to the specific needs of a particular trading strategy.

Thousands of asset types are traded in EVE’s markets. However, as in real-world markets, the frequency of trades and the price range for an asset varies widely according to type. Trading strategies usually prefer liquid asset types, which are those asset types that can be bought or sold at relatively stable prices. Such asset types are more amenable to analysis and are typically easier to buy and sell as needed in the market. Real-world traders use liquidity as one of the prime measures for admitting or excluding asset types from their tradable portfolio. There are many factors that lead to price stability, but often the most important factor is daily volume. Assets which are traded daily at reasonable volume are more likely to have rich pools of buyers and sellers, and prices are more likely to converge to a stable range. Additional criteria, such as having roughly balanced buyers and sellers, may also be important.

In this example, we derive a simple liquidity filter. This is one of the simplest of our preliminary examples, but also one of the most important as a well chosen asset portfolio is key to many strategies. We focus our efforts on the general framework for testing liquidity. This framework is pluggable, allowing different filters to be inserted as needed. We create two example filters to illustrate how to use the framework. You can follow along with this example by downloading the Jupyter Notebook.

For this example, we’ll look for liquid types in The Forge region and we’ll choose to measure liquidity over the 90 days of market snapshots leading up to our reference date. The choice of date range depends on your trading strategy: if your strategy expects recently liquid assets to remain liquid well into the future, then you should select a longer historical date range; if, instead, you only require assets to remain liquid for the next day or so, then you can select a much shorter historical range. Likewise, we could also create a liquidity filter based on order book data instead of market snapshots. This is usually not necessary unless your strategy calls for analyzing liquidity at certain times of day (some market making strategies may find this information useful). The first cell in our notebook sets up are initial parameters: